When U.S. Navy SEALs raided a Pakistan compound on May 2nd, 2011 and

killed Osama bin Laden, it was an almost moonless night. So when

director Kathryn Bigelow sought to re-create the raid in Zero Dark Thirty,

she and DOP Greig Fraser had a very clear mandate to film the scene in

almost pitch darkness. The result is an authentic re-telling of the hunt

for the Al Qaeda leader, but also one that posed a significant

challenge for the visual effects crew from Image Engine, called upon to

create photorealistic stealth helicopters used in the daring raid, as

well as several other key effects in the Oscar-nominated film.

Note: this article contains major plot spoilers

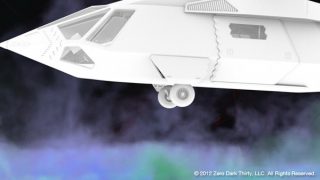

However, the stealth helicopter props were invaluable in providing reference for Image Engine in designing and modeling CG versions. “They were all CNC milled so we got the original 3D data for them which was a huge jumping off point,” says visual effects supervisor Chris Harvey. “Then it was a process of taking them and making them look real, with dents, divots, scratches, grooves and bolts. We’d work on the lookdev until you couldn’t tell the difference.”

One of the hardest aspects of the chopper design was that, by design, they looked like game models. “They’re a few flat polygons with sharp edges,” notes Harvey. “So they kind of look CG anyway – even the real ones. Actually even Kathryn kind of called them ‘gamey’. They were really sensitive to reflection angles. When the helicopter moved, it’d be bright and the next time it’d be black. So we had to do some funky curve reflections and some animated reflection cards that we’d track on, just so they wouldn’t pop on with weird reflections.”

The visual effects team then had three main approaches to deal with dust:

1. In the case where a real helicopter created a performance that Bigelow wanted exactly in the end, Image Engine match-moved the stand-in and then substituted their digital stealth helicopter, embedded it into the plate dust, and then added their own dust sims on top.

2. In other cases, the performance would be tweaked with the digital helicopter. “The advantage of using the real helicopters was that you got a whole bunch of nuances in the motion of the helicopter that would have been really hard to get,” says Harvey. “And the dust interaction, which was awesome, looked real because it was real, other than the stuff we used to help integrate it.”

3. Finally, some shots would rely on throwing away any plate footage and creating helicopter and dust shots from scratch, although of course all the footage aided in animation and dust reference.

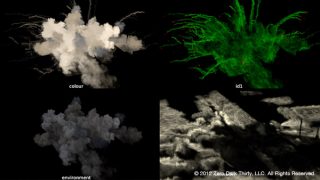

The digital dust was simulated in Houdini. “We built a helicopter dust rig where we’d run a sim to create the rolling vortexes of the dust,” explains Harvey. “We’d also add in any objects to the sim, like a wall, so it would flow realistically.”

And dust turned out to be a crucial method used by Image Engine to reveal the shape of the stealth helicopters, especially when they were shrouded in darkness. “You couldn’t always shape it with say a rim light,” says Harvey, “so we would try and choreograph the dust to reveal the chopper almost as a silhouette. We ended up using non-lighting techniques to add what you would typically do with the lighting anywhere we could – against the sky or a bright part of the wall.”

In some shots there would also be pieces of debris, from paper to styrofoam cups, pop cans and bottles, pieces of paper and plastic – also simulated in Houdini. “So first there’d be a fluid sim for the dust would be would used to drive a series of rigid-body geo, some cloth objects and soft-bodies, depending on whether it was paper or cans,” says Harvey.

The Lone Pine plates were also filmed during the day. And that’s where a further significant challenge lay for Image Engine – turning these daytime shots into night. “In the end that involved a ton of work from our comp team to re-grade all of the plates to look like they were shot at night,” says Harvey.

Rotor blades on the digital helicopters were something the VFX supe played close attention to. “We started with footage that had been shot of the Black Hawks, then we took our CG model and we ran out a really exhaustive series of wedges. We set our rig up so you could literally enter in an RPM value for the rotors, then ran out a series of side-by-side renders against the real footage, running at different RPMs. We found the RPM setting that matched and that became the default value that we plugged in.”

In addition, shooting during the day meant that there were no suitable HDRs that could be taken. Image Engine artists were ultimately required to tweak each helicopter shot on a per-shot basis. And even then, once the DI process began, some shots required re-comping, as Harvey explains:

“We would light everything a stop or two bright so we could bring it down in the DI, but there needed to be a huge amount of collaboration between us and the DI because there was such a narrow band of light level that we had to work with. If we went a point to low, then once it went through the print and a LUT went on it, everything just went black. It was a very fine line. There was a bunch of shots we had to redo because they just couldn’t hold up under projection environments. So at the last minute we had to go in and re-grade and comp 25 shots just because the margins were so thin.”

There are a few daytime shots of the compound, however, and these included digital augmentations such as trees and surrounding mountains. “At night we could get away with not adding them,” says Harvey,” although we did add some distance lights. One of the days that we had the Black Hawks there filming the crash and the take off, I just rode back with them to the military base and we shot a whole bunch of aerial night plates and city lights – 15 minutes of footage of random flickering lights. Comp would just cut them out and piece them in back in as lights for deep backgrounds.”

Firstly, the performance of the crane moving the prop helicopter was deemed too slow. At the same time, some of the shots from the crash sequence were re-choreographed because Bigelow and the filmmakers received new information about what may have happened during the raid. A third factor was related to the lighting response of the prop. “The prop behaved a certain way in the lighting conditions on the set,” explains Harvey. “It always looked a little too source-y for Kathryn, like there was a moon somewhere, or that there was too big a hit. She wanted everything to be always moonless, ambient, without a really strong key or backlight.”

This meant that Image Engine crafted the crash with a digital stealth helicopter, and also completed other exterior scenes of the helicopters at the compound that had originally been filmed with the prop. “We went through hours of footage of what we shot there and we were looking for plates that we could cut the rig out at a nice angle, and then we would put our own performance in,” says Harvey. “We ended up constructing this whole new sequence for Kathryn, and went through a couple of iterations to get what she wanted.”

Bigelow’s request was for a ‘visceral, in-your-face moment’ as the crash occurs. “A lot of that came through dust and debris thrown into camera,” says Harvey. “When the tail goes onto the back wall, both of those shots are entirely digital in the end. We animated the action, which was cached out, given to the Houdini guys, and they would run a rigid-body destruction simulation across the top of the wall and the barbed wire to rip off the concrete and wire. That would be piped back into the animation to deform and crumple the tail a little bit. Then all that would be passed back into Maya for lighting and rendering. Then dust sims were put on top of that. Then there would be piles of dirt and sound and pebbles that got kicked up to make it in your face.”

This was achieved as a practical explosion of one of the prop stealths orchestrated by special effects supervisor Richard Stutsman (who had previously worked with Bigelow on The Hurt Locker). “It was pretty awesome,” exclaims Harvey. “We’d been shooting for weeks and we were right there on the edge of this little town and everyone was always out checking things, especially this time because we had Black Hawks flying around – it was also a little bit tense because we were a mile away from the Dead Sea and right on the border of Israel.”

Image Engine made some slight augmentations to the final explosion shot, replacing the initial view of the helicopter in the plate because the prop had been cut up to fit the explosives in, and then adding some flying rotors and debris, along with the remaining flying helicopters. The shot was also given a night grade since it had been filmed at dusk.

It is at Chapman that a suicide bomber stalls the progress of Maya’s search by killing her fellow agent Jessica and others in a car bombing. The explosion is seen in two shots. Firstly, the low angle view has smoke and debris filling the frame. For that, production shot several different passes with multiple cameras – a clean plate, dust canon, an air canon shooting into people, a fireball pass, a clean car and the car blowing up. Richard Stutsman provided the practical explosion.

Image Engine then took those elements into comp and layered the shot. “We did a little augmentation of the environment immediately around the car,” adds Harvey. “In order to shoot all those passes takes a little time so the sun would change position and the shadows would be falling in different areas. So there was some 2D re-lighting of the shot. Then down the street that’s all a matte painting extension.”

On the high and wide shot, the same passes were all filmed, but it was decided the explosion needed to have more impact. Image Engine replaced and matched the practical shot with a digital version created in Houdini, also implementing shockwaves, shattering glass and integration to the surrounding vehicles and buildings.

The 2008 Islamabad Marriott Hotel attack is also shown in the film, with the bombing survived by Maya and Jessica as they dine in a hotel restaurant. “Richard Stutsman did an amazing job on that explosion,” notes Harvey. “We just had to do a fair amount of paint-outs – he had pull wires on tables, chairs, people. We did a bit of augmentation in terms of extra fill smoke and a little grading and some fire enhancement to make it feel like there were some core flames. Then Kathryn got us to make a couple of wine glasses and bottles fall over which hadn’t in the blast – so we went in and painted out any remaining objects on the tables that didn’t tip over. ”

Note: this article contains major plot spoilers

The helicopters – avoiding the game look

Two full-sized stealth helicopters were built in London for the film. Initially, these were designed to be filmed on large gimbals for shots of the SEALs traveling to the compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan and for exterior views, where rotors and environments would be added. Ultimately, due to changes in the action and lighting issues (discussed below), most of the helicopter exteriors were achieved as Image Engine creations.However, the stealth helicopter props were invaluable in providing reference for Image Engine in designing and modeling CG versions. “They were all CNC milled so we got the original 3D data for them which was a huge jumping off point,” says visual effects supervisor Chris Harvey. “Then it was a process of taking them and making them look real, with dents, divots, scratches, grooves and bolts. We’d work on the lookdev until you couldn’t tell the difference.”

One of the hardest aspects of the chopper design was that, by design, they looked like game models. “They’re a few flat polygons with sharp edges,” notes Harvey. “So they kind of look CG anyway – even the real ones. Actually even Kathryn kind of called them ‘gamey’. They were really sensitive to reflection angles. When the helicopter moved, it’d be bright and the next time it’d be black. So we had to do some funky curve reflections and some animated reflection cards that we’d track on, just so they wouldn’t pop on with weird reflections.”

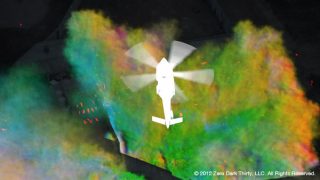

The dust effect

For scenes of the stealth helicopters taking off, landing, and later for a crash sequence, Image Engine had another major challenge – dust. But Harvey took the bold step of recommending to production that they shoot real helicopters – Black Hawks – that would later be replaced with the stealth versions. “Well, they straight away said, ‘What about the dust?’ I basically said it was better to get real interaction with the environment and we’ll replace what we have to replace.”The visual effects team then had three main approaches to deal with dust:

1. In the case where a real helicopter created a performance that Bigelow wanted exactly in the end, Image Engine match-moved the stand-in and then substituted their digital stealth helicopter, embedded it into the plate dust, and then added their own dust sims on top.

2. In other cases, the performance would be tweaked with the digital helicopter. “The advantage of using the real helicopters was that you got a whole bunch of nuances in the motion of the helicopter that would have been really hard to get,” says Harvey. “And the dust interaction, which was awesome, looked real because it was real, other than the stuff we used to help integrate it.”

3. Finally, some shots would rely on throwing away any plate footage and creating helicopter and dust shots from scratch, although of course all the footage aided in animation and dust reference.

The digital dust was simulated in Houdini. “We built a helicopter dust rig where we’d run a sim to create the rolling vortexes of the dust,” explains Harvey. “We’d also add in any objects to the sim, like a wall, so it would flow realistically.”

And dust turned out to be a crucial method used by Image Engine to reveal the shape of the stealth helicopters, especially when they were shrouded in darkness. “You couldn’t always shape it with say a rim light,” says Harvey, “so we would try and choreograph the dust to reveal the chopper almost as a silhouette. We ended up using non-lighting techniques to add what you would typically do with the lighting anywhere we could – against the sky or a bright part of the wall.”

In some shots there would also be pieces of debris, from paper to styrofoam cups, pop cans and bottles, pieces of paper and plastic – also simulated in Houdini. “So first there’d be a fluid sim for the dust would be would used to drive a series of rigid-body geo, some cloth objects and soft-bodies, depending on whether it was paper or cans,” says Harvey.

Journey to Pakistan

After taking off from Afghanistan, the SEALs fly over the border to Abbottabad in a series of shots made up of real aerial backgrounds filmed over Lone Pine, CA, and Image Engine digital stealth helicopters. Harvey lead the shoot using three Eurocopters through a number of canyons and above varied terrain in the area. “We shot with real plates rather than go all digital because it really helped provide something authentic,” says Harvey. “It removed a lot of the guessing game and back and forth of, ‘Well I think a real helicopter would bank here’. We altered the animation a little bit because they were smaller helicopters. We would track them and then dampen the animation curves so they all seemed heavier.”The Lone Pine plates were also filmed during the day. And that’s where a further significant challenge lay for Image Engine – turning these daytime shots into night. “In the end that involved a ton of work from our comp team to re-grade all of the plates to look like they were shot at night,” says Harvey.

Rotor blades on the digital helicopters were something the VFX supe played close attention to. “We started with footage that had been shot of the Black Hawks, then we took our CG model and we ran out a really exhaustive series of wedges. We set our rig up so you could literally enter in an RPM value for the rotors, then ran out a series of side-by-side renders against the real footage, running at different RPMs. We found the RPM setting that matched and that became the default value that we plugged in.”

The compound

Day-for-night shots were also required for scenes of the SEALs arriving at the compound. In Jordan, real Black Hawks standing in for the digital stealth helicopters were filmed on a life-sized set (designed with the help of Framestore concepts and 3D models) during a narrow dusk window from 4pm to 5.30pm due to costs and safety concerns of having to fly with night vision. “In some cases,” says Harvey, “you’d have the sunset which gave you a fancy magic hour lighting conditions that we’d have to go in and do sky replacements and re-grading and all of that.”In addition, shooting during the day meant that there were no suitable HDRs that could be taken. Image Engine artists were ultimately required to tweak each helicopter shot on a per-shot basis. And even then, once the DI process began, some shots required re-comping, as Harvey explains:

“We would light everything a stop or two bright so we could bring it down in the DI, but there needed to be a huge amount of collaboration between us and the DI because there was such a narrow band of light level that we had to work with. If we went a point to low, then once it went through the print and a LUT went on it, everything just went black. It was a very fine line. There was a bunch of shots we had to redo because they just couldn’t hold up under projection environments. So at the last minute we had to go in and re-grade and comp 25 shots just because the margins were so thin.”

There are a few daytime shots of the compound, however, and these included digital augmentations such as trees and surrounding mountains. “At night we could get away with not adding them,” says Harvey,” although we did add some distance lights. One of the days that we had the Black Hawks there filming the crash and the take off, I just rode back with them to the military base and we shot a whole bunch of aerial night plates and city lights – 15 minutes of footage of random flickering lights. Comp would just cut them out and piece them in back in as lights for deep backgrounds.”

The crash

As one of the stealth helicopters hovers over a compound wall it is caught in its own downwash before the pilot is able to bring it to the ground. No one is injured, but the tail ends up resting on the wall. On the Jordan set, the crash was filmed with the prop helicopter on a crane. However, several factors resulted in Image Engine re-imagining the sequence.Firstly, the performance of the crane moving the prop helicopter was deemed too slow. At the same time, some of the shots from the crash sequence were re-choreographed because Bigelow and the filmmakers received new information about what may have happened during the raid. A third factor was related to the lighting response of the prop. “The prop behaved a certain way in the lighting conditions on the set,” explains Harvey. “It always looked a little too source-y for Kathryn, like there was a moon somewhere, or that there was too big a hit. She wanted everything to be always moonless, ambient, without a really strong key or backlight.”

This meant that Image Engine crafted the crash with a digital stealth helicopter, and also completed other exterior scenes of the helicopters at the compound that had originally been filmed with the prop. “We went through hours of footage of what we shot there and we were looking for plates that we could cut the rig out at a nice angle, and then we would put our own performance in,” says Harvey. “We ended up constructing this whole new sequence for Kathryn, and went through a couple of iterations to get what she wanted.”

Bigelow’s request was for a ‘visceral, in-your-face moment’ as the crash occurs. “A lot of that came through dust and debris thrown into camera,” says Harvey. “When the tail goes onto the back wall, both of those shots are entirely digital in the end. We animated the action, which was cached out, given to the Houdini guys, and they would run a rigid-body destruction simulation across the top of the wall and the barbed wire to rip off the concrete and wire. That would be piped back into the animation to deform and crumple the tail a little bit. Then all that would be passed back into Maya for lighting and rendering. Then dust sims were put on top of that. Then there would be piles of dirt and sound and pebbles that got kicked up to make it in your face.”

Night vision

Peppered throughout the tense raid sequence are several night vision point of view shots. To get these in-camera, DOP Greig Fraser bolted night vision lenses onto the ARRI Alexas used for filming, and relied on infrared lights. Occasionally, Image Engine was required to add a CG element into one of these shots and so had to match the lenses. “There were a few different ones used that had different scaling and noise on them,” says Harvey. “So just like you would shoot lens grids, gray balls, and gray charts to get your film grain with regular lenses, we shot it again with all those lenses.”Leaving the chopper behind

The mission, which was code-named Operation Neptune Spear, is a success and bin Laden is killed and his body taken back to the Afghan base. Before leaving, the SEALs destroy the downed stealth helicopter.This was achieved as a practical explosion of one of the prop stealths orchestrated by special effects supervisor Richard Stutsman (who had previously worked with Bigelow on The Hurt Locker). “It was pretty awesome,” exclaims Harvey. “We’d been shooting for weeks and we were right there on the edge of this little town and everyone was always out checking things, especially this time because we had Black Hawks flying around – it was also a little bit tense because we were a mile away from the Dead Sea and right on the border of Israel.”

Image Engine made some slight augmentations to the final explosion shot, replacing the initial view of the helicopter in the plate because the prop had been cut up to fit the explosives in, and then adding some flying rotors and debris, along with the remaining flying helicopters. The shot was also given a night grade since it had been filmed at dusk.

Setting the scene

Of course, the compound raid sequence is the climax of the film – but preceding this is the story of CIA agent Maya (Jessica Chastain) as she attempts to zero in on bin Laden’s whereabouts. Image Engine completed various visual effects for environments, military bases and several bombings.Explosion at Camp Chapman

Wide shots of military bases in Afghanistan, including one of Camp Chapman, made use of reference photography and on-set elements. “We would do a layout pass of each of the environments,” says Harvey, “and that was with gray-shaded boxes and a quick matte painted paint-over. And we’d get buy-off on building density, locations, cars. Then Kathryn wouldn’t want to see it again until it was mostly done. The Chapman base had 400 digi-doubles in the background, cars with dust in the background – just to make it feel like a bustling base.”It is at Chapman that a suicide bomber stalls the progress of Maya’s search by killing her fellow agent Jessica and others in a car bombing. The explosion is seen in two shots. Firstly, the low angle view has smoke and debris filling the frame. For that, production shot several different passes with multiple cameras – a clean plate, dust canon, an air canon shooting into people, a fireball pass, a clean car and the car blowing up. Richard Stutsman provided the practical explosion.

Image Engine then took those elements into comp and layered the shot. “We did a little augmentation of the environment immediately around the car,” adds Harvey. “In order to shoot all those passes takes a little time so the sun would change position and the shadows would be falling in different areas. So there was some 2D re-lighting of the shot. Then down the street that’s all a matte painting extension.”

On the high and wide shot, the same passes were all filmed, but it was decided the explosion needed to have more impact. Image Engine replaced and matched the practical shot with a digital version created in Houdini, also implementing shockwaves, shattering glass and integration to the surrounding vehicles and buildings.

London and Islamabad bombings

In a late addition to Image Engine’s workload, the July 2005 terrorist attack on London is highlighted in a scene depicting the explosion of a double-decker bus. Originally intended as just hinting at the devastation, the explosion is shown more fully as the bus passes a clump of trees. “We organized our own pyro shoot here on a stage and blew some stuff up that we used for elements,” says Harvey. “Then from some of those cameras from the Chapman explosion, we went in and cut out stuff we could use. Then like a jigsaw puzzle we built up the explosion that happens behind the hedge and the trees for the bus.”The 2008 Islamabad Marriott Hotel attack is also shown in the film, with the bombing survived by Maya and Jessica as they dine in a hotel restaurant. “Richard Stutsman did an amazing job on that explosion,” notes Harvey. “We just had to do a fair amount of paint-outs – he had pull wires on tables, chairs, people. We did a bit of augmentation in terms of extra fill smoke and a little grading and some fire enhancement to make it feel like there were some core flames. Then Kathryn got us to make a couple of wine glasses and bottles fall over which hadn’t in the blast – so we went in and painted out any remaining objects on the tables that didn’t tip over. ”