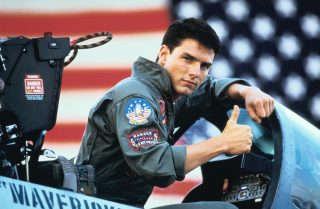

Before sadly passing away in 2012, Top Gun director Tony

Scott oversaw the stereo conversion of his defining 1986 film, about to

be released in IMAX 3D and on Blu-ray/DVD. We talk to Legend3D founder,

chief creative officer and chief technology officer Dr. Barry Sandrew

about the art behind the conversion. And we also revisit the ingenious

miniature and in-camera effects of the film with special photographic

effects supervisor Gary Gutierrez.

Download Video

Download Video

The negative was scanned by EFILM, who oversampled at 6K using ARRI scanners in High Dynamic Range mode, then recorded at 4K by Company3 who extracted as 2K files. “Company3 then trimmed the files nondestructively in preparation for Legend3D’s restoration and conversion that was performed with a working LUT provided by Company3,” says Sandrew.

Download Video

Download Video

The depth script was far from conservative, with Legend’s conversion

team – led by Tony Baldridge, stereo VFX supervisor, Cyrus Gladstone,

stereographer and Adam Gering, compositing supervisor – ‘exploiting’ the

new scan so that audiences would ultimately feel like they were

experiencing Top Gun for the first time. “[Tony] loved the

flight scenes and wanted the intensity of those moments to resonate with

audience’s adrenaline,” says Sandrew. “He felt that they had to be

immersed in the action. We had the freedom to set the convergence

throughout the film, which allowed us to break the boundaries set by

filming in 3D. Cyrus correctly pointed out that placing the jets off

screen would not be distracting to the viewer if there was sufficient

fluidity from shot to shot. Sometimes we would ‘Multi-Rig’ the

convergence between shots to not distract from the story.

For more sensitive moments, such as Goose’s accident, Legend pulled back on the immersion effect. “This is another case where Cyrus made a creative call that I agreed with 100%,” says Sandrew. “He set this scene up with an overall high depth bracket to start off, almost causing an uncomfortable experience for the viewer then we eased into an observation standpoint so as not to distract from the impact of this important moment in the story.”

Sandrew suggests that this different approach results in incredibly precise detail. “In fact,” he says, “the masking is so precise that features most people take for granted, like eye highlights, are always inset by a fraction of a pixel, the size of which is dependent on the distance of the actor from the camera.” A new addition to Legend’s tech arsenal is the ability to view a segmented shot that has been placed in depth in full motion within the stereo conversion environment and simultaneously on an accompanying stereo monitor, allowing on the fly adjustments.

It turned out that Legend was not present during Tony Scott’s screening of the first converted reel (which occurred privately with Pat Sandston, Associate Producer of Jerry Bruckheimer Films). But there was little to worry about. “At the conclusion of that very first screening of Top Gun,” says Sandrew, “Pat informed us that Tony was blown away by the experience of seeing his film in stereo for the first time. As a consequence Tony felt comfortable giving us complete creative freedom on the full conversion process and was content to screen each reel as we completed them in stereo depth.”

Cockpit POVs were particularly challenging for Legend since they were often tight close-ups of the pilots. “They required both realistic depth for the interior of cockpits while maintaining accurate volume in the actors faces,” explains Sandrew. “Tony Scott came to realize that the cockpit shots could not have been filmed in the same manner with stereo rigs had they been available 27 years ago.”

Confounding the issue were jet canopy reflections wrapping around the pilots that needed to be placed in depth with the appropriate transparencies. “To handle this problem accurately, we visited the Midway Aircraft Carrier in San Diego so we could sit in F14s to determine how reflections and accompanying jets flying in the background should be handled in the conversion process,” says Sandrew. “One thing we determined from the F14s is that fighter jets flying in the background appeared somewhat distorted at the maximally curved edges of the canopy due to refraction. This required a different depth treatment than jets observed from different portions of the canopy.”

“Tony Baldridge is always quick to point out that long lenses were used extensively in Top Gun,” adds Sandrew. “This tends to compress space, flatting the subject in frame. While this can be desirable in a 2D film, for a 3D film that is shot ‘natively’ it can be a serious issue. However, with 2D to 3D conversion the sky is the limit (no pun intended). We are lens agnostic and can create depth that would otherwise be impossible through conventional capture.”

Dogfights

The frenetic dogfights and aerial scenes in Top Gun were achieved with unprecedented access to the US Navy, second unit photography and some ingenious miniature plane special effects photography (see below). In order to convert the fast action shots and the associated atmospheric effects for explosions, smoke and clouds, Sandrew says Legend relied on its proprietary toolset. However, he notes also that the original framing of the shots proved incredibly suitable for 3D. “Twenty-six years ago when Tony Scott was lensing Top Gun for the big screen, the idea of 3D was the farthest thing from his mind,” says Sandrew. “But as I remarked to him at the wrap, the way he composited each shot was ideal for stereo. The fighter jets were for the most part in center screen, which improves the effectiveness of negative stereo placement in front of the screen.”

Legend also sought professional feedback on the aerial shot conversions, an easy task with Miramar Air Force Base literally just down the road from the San Diego studio. “We often invited active and retired Top Gun pilots to screen the dimensionalized aerial shots in one of Legend3D’s RealD theaters so we could assess the accuracy of transient vertigo that resulting from the combat flight sequences,” says Sandrew. “We wanted to simulate the natural sense of vertigo during combat flight without making the audience sick. Fortunately the aerial shots were fairly quick so we knew that any sense of vertigo we allowed would be minimal but highly effective.”

“In fact upon leaving the theater one retired pilot thanked me for reminding him what a barrel roll in an F14 felt like,” Sandrew adds. “I believe that the way we handled the stereo conversion really brought a greater authenticity to those shots, giving the audience a true sense of what it felt like to be flying a fighter jet in a dog fight situation. I had the distinct pleasure of screening the fighter jet scenes in 3D with Clay Lacy, an icon in aviation history and the original aerial photographer on Top Gun. Clay was amazed that we were able to enhance his cinematography in three dimensions. He was extremely comfortable with the stereo conversion and thought the realism we were able to create was simply unbelievable.”

“And Tony Scott loved to use long dolly shots of actors walking toward the camera,” he adds. “One such shot involved 1055 frames of Maverick and Charlie walking toward the tracking camera down a long hallway, stopping at both the beginning and end of the shot for prolonged dialog. Once again, back lit, the profiles and hair against the ever-changing verticals in the background were a challenge.”

“There was this realism in having ragged photography,” recalls Gutierrez, who spoke to fxguide about his memories of working on Top Gun. “Ironically, after The Right Stuff and Top Gun,

computer moco systems and CG solutions did the same thing we did –

which was to imitate a certain raggedness of camerawork for action

shots. It just added more vitality to the look of the image, and had

more of a sense of less perfect-ness.”

“There was this realism in having ragged photography,” recalls Gutierrez, who spoke to fxguide about his memories of working on Top Gun. “Ironically, after The Right Stuff and Top Gun,

computer moco systems and CG solutions did the same thing we did –

which was to imitate a certain raggedness of camerawork for action

shots. It just added more vitality to the look of the image, and had

more of a sense of less perfect-ness.”

The result, says Gutierrez, was that this approach made it blend in with the second unit and aerial photography in Top Gun. Most of those shots were somewhat messy and fast-moving, owing to the method of capture and Tony Scott’s desired style. Coupled with fast edits for the aerial scenes, the shots intercut and most people did not know what was real and what was a miniature.

Models: scores of model planes were crafted,

included various sizes of F-14′s, F-5s and Russian MiGs repurposed from

RC models and model kits.

Models: scores of model planes were crafted,

included various sizes of F-14′s, F-5s and Russian MiGs repurposed from

RC models and model kits.

Filming location: this actually occurred on a hilltop location in Oakland, California, surrounded by a then un-built housing development, providing space for explosions and clear background sky views (only one gray day necessitated the use of HMI lights and a large sky blue backing).

Shooting: since bluescreen or motion control was not being used, shots were acquired in several ways, including simple handheld moves. Planes were suspended on wires and rods or simply dropped from man-lifts (which were also used to film from). Rick Fichter was the DOP for USFX.

Shaky cam: a purposely ragged style of shooting mimicked specific styles of camera movement that would be seen in actual photography of the full scale objects. The effects team took this one step further by bolting on a drill attached to an off-set piece of wood to the camera in order to give the shots an unbalanced and ‘shaky feel’ – and it wasn’t long before other effects shops were using a similar technique. “We would see it in the very next thing ILM did, one of the Star Trek films,” says Gutierrez. “They actually started shaking the camera in their moco shots, adding roughness and a looser kind of look and vibration. And it’s now become part of the bag of techniques in CG to take the curse off of a shot, to add in deliberate imperfections that you might get in live action photography.”

Flat spin: Maverick and Goose’s fall into the ocean included a shot of their plane spinning right down towards the camera lens protected by a Lexan. For that shot, a grip took a Tomcat model up on a man lift and gave it a slight spin before releasing (and in the process winning a $5 bet that he couldn’t hit the camera – which he did twice).

Tracer fire: to simulate the look of tracer fire, a rig was set up to shoot small mortars of magnesium through the air past the model plane. Ultimately deemed unsuccessful, the shots were eventually achieved mostly with traditional animation and rotoscoping (something also used for cockpit head-up displays and a Sidewinder missile hit on a MiG in the film’s final battle).

Explosions: For missile hits, the effects team rigged pyro on the planes using napthalene, black powder and gasoline. “We shoved these eight foot models on fire with pyrotechnic chemicals and off of the ramp a 100 feet in the sky,” recalls Gutierrez. “Someone had devised a big boxing ring sized pad of foam and the first time we tried that it caught on fire! But luckily no-one was injured.”

All images and clips copyright Paramount Pictures. All rights reserved

00:00 | 00:00

Watch the trailer for the IMAX 3D and Blu-ray 3D re-release of Top Gun.

Converting Top Gun

Preparing the film

Top Gun had been shot on Super 35mm film, so the first requirement was to scan the original negative. Digital mastering expert Garrett J. Smith acted as a liaison to Legend3D during the scanning process. “In his opinion,” says Sandrew, “the film had been properly handled over the years and because it was shot Super 35, there was less wear and tear on the negative than others from that era.”The negative was scanned by EFILM, who oversampled at 6K using ARRI scanners in High Dynamic Range mode, then recorded at 4K by Company3 who extracted as 2K files. “Company3 then trimmed the files nondestructively in preparation for Legend3D’s restoration and conversion that was performed with a working LUT provided by Company3,” says Sandrew.

Creating a depth script

The Legend team then crafted a ‘depth script’ for the film which, as Sandrew explains, was designed to follow the pulse of the story much like a music score. “Most people rarely notice the music score in a movie but when executed well, we are very much influenced by it,” he says. “Our goal is the same in stereo conversion. We want to avoid creating a situation where 3D becomes the story. In fact, the audience should be able to lose themselves in the film, forgetting that they are watching a 3D movie. However, we do want to use conversion to immerse the audience and enhance their emotional and visceral reaction to the storyline.”

00:00 | 00:00

Scenes with Charlie (Kelly McGillis) and

other actors were not necessarily easy to convert, owing to flyaway

hairs and long tracking shots.

For more sensitive moments, such as Goose’s accident, Legend pulled back on the immersion effect. “This is another case where Cyrus made a creative call that I agreed with 100%,” says Sandrew. “He set this scene up with an overall high depth bracket to start off, almost causing an uncomfortable experience for the viewer then we eased into an observation standpoint so as not to distract from the impact of this important moment in the story.”

Conversion tech

Legend3D is unlike most other conversion houses in its technical approach to stereo work. Firstly, the company does not use roto to segment data in each image. “Instead,” explains Sandrew, “we use a form of masking that has evolved over the past 20 years from the digital colorization process that I invented in 1987. It does not involve splines or Beziers but is more of an organic process where the stereo artist creates a series of facets that best defines the bone structure of each actor’s face.”

Check out fxguide’s previous in-depth look at the art of stereo conversion in our feature article here.

“The appropriate volume of the actor’s head is based on pre-prepared

templates that establishes both the correct spatial relations and

relative proportions of all the facial and head features,” adds Sandrew.

“This process is in stark contrast to modeling and projection

techniques common to the conversion industry. The facets we create are

used to reconstruct the faces within one of two virtual stereo stages

complete with multiple cameras. One stage automatically creates natural

falloff of depth with distance from the camera, while the other allows

for more creative freedom in stereo positioning.”Sandrew suggests that this different approach results in incredibly precise detail. “In fact,” he says, “the masking is so precise that features most people take for granted, like eye highlights, are always inset by a fraction of a pixel, the size of which is dependent on the distance of the actor from the camera.” A new addition to Legend’s tech arsenal is the ability to view a segmented shot that has been placed in depth in full motion within the stereo conversion environment and simultaneously on an accompanying stereo monitor, allowing on the fly adjustments.

The first review

“In the beginning we had no idea what Tony’s expectations were for the film,” recalls Sandrew. “After all, he was new to the conversion process and I’m sure he was somewhat skeptical that the story of his 28 year old iconic film could be enhanced with the introduction of a third dimension. Consequently, we were initially given free reign over the look and feel of the first reel so that Tony could see whether this was actually going to work.”It turned out that Legend was not present during Tony Scott’s screening of the first converted reel (which occurred privately with Pat Sandston, Associate Producer of Jerry Bruckheimer Films). But there was little to worry about. “At the conclusion of that very first screening of Top Gun,” says Sandrew, “Pat informed us that Tony was blown away by the experience of seeing his film in stereo for the first time. As a consequence Tony felt comfortable giving us complete creative freedom on the full conversion process and was content to screen each reel as we completed them in stereo depth.”

Converting key scenes

Inside the cockpitsCockpit POVs were particularly challenging for Legend since they were often tight close-ups of the pilots. “They required both realistic depth for the interior of cockpits while maintaining accurate volume in the actors faces,” explains Sandrew. “Tony Scott came to realize that the cockpit shots could not have been filmed in the same manner with stereo rigs had they been available 27 years ago.”

Confounding the issue were jet canopy reflections wrapping around the pilots that needed to be placed in depth with the appropriate transparencies. “To handle this problem accurately, we visited the Midway Aircraft Carrier in San Diego so we could sit in F14s to determine how reflections and accompanying jets flying in the background should be handled in the conversion process,” says Sandrew. “One thing we determined from the F14s is that fighter jets flying in the background appeared somewhat distorted at the maximally curved edges of the canopy due to refraction. This required a different depth treatment than jets observed from different portions of the canopy.”

“Tony Baldridge is always quick to point out that long lenses were used extensively in Top Gun,” adds Sandrew. “This tends to compress space, flatting the subject in frame. While this can be desirable in a 2D film, for a 3D film that is shot ‘natively’ it can be a serious issue. However, with 2D to 3D conversion the sky is the limit (no pun intended). We are lens agnostic and can create depth that would otherwise be impossible through conventional capture.”

Dogfights

The frenetic dogfights and aerial scenes in Top Gun were achieved with unprecedented access to the US Navy, second unit photography and some ingenious miniature plane special effects photography (see below). In order to convert the fast action shots and the associated atmospheric effects for explosions, smoke and clouds, Sandrew says Legend relied on its proprietary toolset. However, he notes also that the original framing of the shots proved incredibly suitable for 3D. “Twenty-six years ago when Tony Scott was lensing Top Gun for the big screen, the idea of 3D was the farthest thing from his mind,” says Sandrew. “But as I remarked to him at the wrap, the way he composited each shot was ideal for stereo. The fighter jets were for the most part in center screen, which improves the effectiveness of negative stereo placement in front of the screen.”

Legend also sought professional feedback on the aerial shot conversions, an easy task with Miramar Air Force Base literally just down the road from the San Diego studio. “We often invited active and retired Top Gun pilots to screen the dimensionalized aerial shots in one of Legend3D’s RealD theaters so we could assess the accuracy of transient vertigo that resulting from the combat flight sequences,” says Sandrew. “We wanted to simulate the natural sense of vertigo during combat flight without making the audience sick. Fortunately the aerial shots were fairly quick so we knew that any sense of vertigo we allowed would be minimal but highly effective.”

“In fact upon leaving the theater one retired pilot thanked me for reminding him what a barrel roll in an F14 felt like,” Sandrew adds. “I believe that the way we handled the stereo conversion really brought a greater authenticity to those shots, giving the audience a true sense of what it felt like to be flying a fighter jet in a dog fight situation. I had the distinct pleasure of screening the fighter jet scenes in 3D with Clay Lacy, an icon in aviation history and the original aerial photographer on Top Gun. Clay was amazed that we were able to enhance his cinematography in three dimensions. He was extremely comfortable with the stereo conversion and thought the realism we were able to create was simply unbelievable.”

The IMAX 3D release of Top Gun begins on Feb 8th, and the Blu-ray is available from February 19th.

The hardest shots are not what you think

When asked which shots were the most challenging to convert, Sandrew says they were the ones people would consider the easiest. “Charlie with her wild hair and Maverick sitting in the bar, their profiles backlit complete with light spill, posed a challenge to our compositing artists who were tasked with maintaining fine flyaway hair while eliminating stretching artifacts from the conversion process.”“And Tony Scott loved to use long dolly shots of actors walking toward the camera,” he adds. “One such shot involved 1055 frames of Maverick and Charlie walking toward the tracking camera down a long hallway, stopping at both the beginning and end of the shot for prolonged dialog. Once again, back lit, the profiles and hair against the ever-changing verticals in the background were a challenge.”

Realism from raggedness – the effects of Top Gun

Top Gun’s special photographic effects supervisor Gary Gutierrez recalls ‘bucking the system’ when he and artists from Colossal Pictures/USFX helped realize the aerial dogfights for the film. Specifically, the team resisted the use of bluescreen motion control – a hot effects technique at the time – and instead went for a more classical in-camera approach to shoot miniature planes and effects. It was something they had also done successfully for Philip Kaufman’s The Right Stuff (1983).

The Top Gun effects crew. This photo was taken on the last day of shooting, December 24th, 1985. Courtesy Gary Gutierrez.

The result, says Gutierrez, was that this approach made it blend in with the second unit and aerial photography in Top Gun. Most of those shots were somewhat messy and fast-moving, owing to the method of capture and Tony Scott’s desired style. Coupled with fast edits for the aerial scenes, the shots intercut and most people did not know what was real and what was a miniature.

Physical effects

So what were the effects solutions used for Top Gun? Here’s a list of just some of the clever ways shots were achieved (for detailed information, check out Cinefex #29 or see The Making of ‘Top Gun’ featurette on the Top Gun Blu-ray/DVD).

Shooting

at Oakland. Screenshot from ‘The Making of Top Gun’ featurette on Top

Gun Blu-ray/DVD. Copyright Paramount Pictures. All rights reserved.

The

drill attachment for ‘shaky cam’. Screenshot from ‘The Making of Top

Gun’ featurette on Top Gun Blu-ray/DVD. Copyright Paramount Pictures.

All rights reserved.

A

falling plane is dropped from a man-lift. Screenshot from ‘The Making

of Top Gun’ featurette on Top Gun Blu-ray/DVD. Copyright Paramount

Pictures. All rights reserved.

Filming location: this actually occurred on a hilltop location in Oakland, California, surrounded by a then un-built housing development, providing space for explosions and clear background sky views (only one gray day necessitated the use of HMI lights and a large sky blue backing).

Shooting: since bluescreen or motion control was not being used, shots were acquired in several ways, including simple handheld moves. Planes were suspended on wires and rods or simply dropped from man-lifts (which were also used to film from). Rick Fichter was the DOP for USFX.

Shaky cam: a purposely ragged style of shooting mimicked specific styles of camera movement that would be seen in actual photography of the full scale objects. The effects team took this one step further by bolting on a drill attached to an off-set piece of wood to the camera in order to give the shots an unbalanced and ‘shaky feel’ – and it wasn’t long before other effects shops were using a similar technique. “We would see it in the very next thing ILM did, one of the Star Trek films,” says Gutierrez. “They actually started shaking the camera in their moco shots, adding roughness and a looser kind of look and vibration. And it’s now become part of the bag of techniques in CG to take the curse off of a shot, to add in deliberate imperfections that you might get in live action photography.”

Flat spin: Maverick and Goose’s fall into the ocean included a shot of their plane spinning right down towards the camera lens protected by a Lexan. For that shot, a grip took a Tomcat model up on a man lift and gave it a slight spin before releasing (and in the process winning a $5 bet that he couldn’t hit the camera – which he did twice).

Tracer fire: to simulate the look of tracer fire, a rig was set up to shoot small mortars of magnesium through the air past the model plane. Ultimately deemed unsuccessful, the shots were eventually achieved mostly with traditional animation and rotoscoping (something also used for cockpit head-up displays and a Sidewinder missile hit on a MiG in the film’s final battle).

Explosions: For missile hits, the effects team rigged pyro on the planes using napthalene, black powder and gasoline. “We shoved these eight foot models on fire with pyrotechnic chemicals and off of the ramp a 100 feet in the sky,” recalls Gutierrez. “Someone had devised a big boxing ring sized pad of foam and the first time we tried that it caught on fire! But luckily no-one was injured.”

Through the viewfinder

“There was a real pleasure that all the cameramen enjoyed in shooting the effects the way we did,” says Gutierrez, “which was finding your shot looking through the viewfinder. That job was starting to be taken away at that point. There’s nothing like a viewfinder and a magic little window to inspire. The world of CG, which I have great respect for and use a lot, does have its limitations. You may have a happy accident every now and then but circumstances are not geared for having them. It’s sometimes too perfect.”All images and clips copyright Paramount Pictures. All rights reserved